Death’s Door: Design & Sound of Reaping

Today we’re taking a look at the game Death’s Door, in terms of its design and sounds.

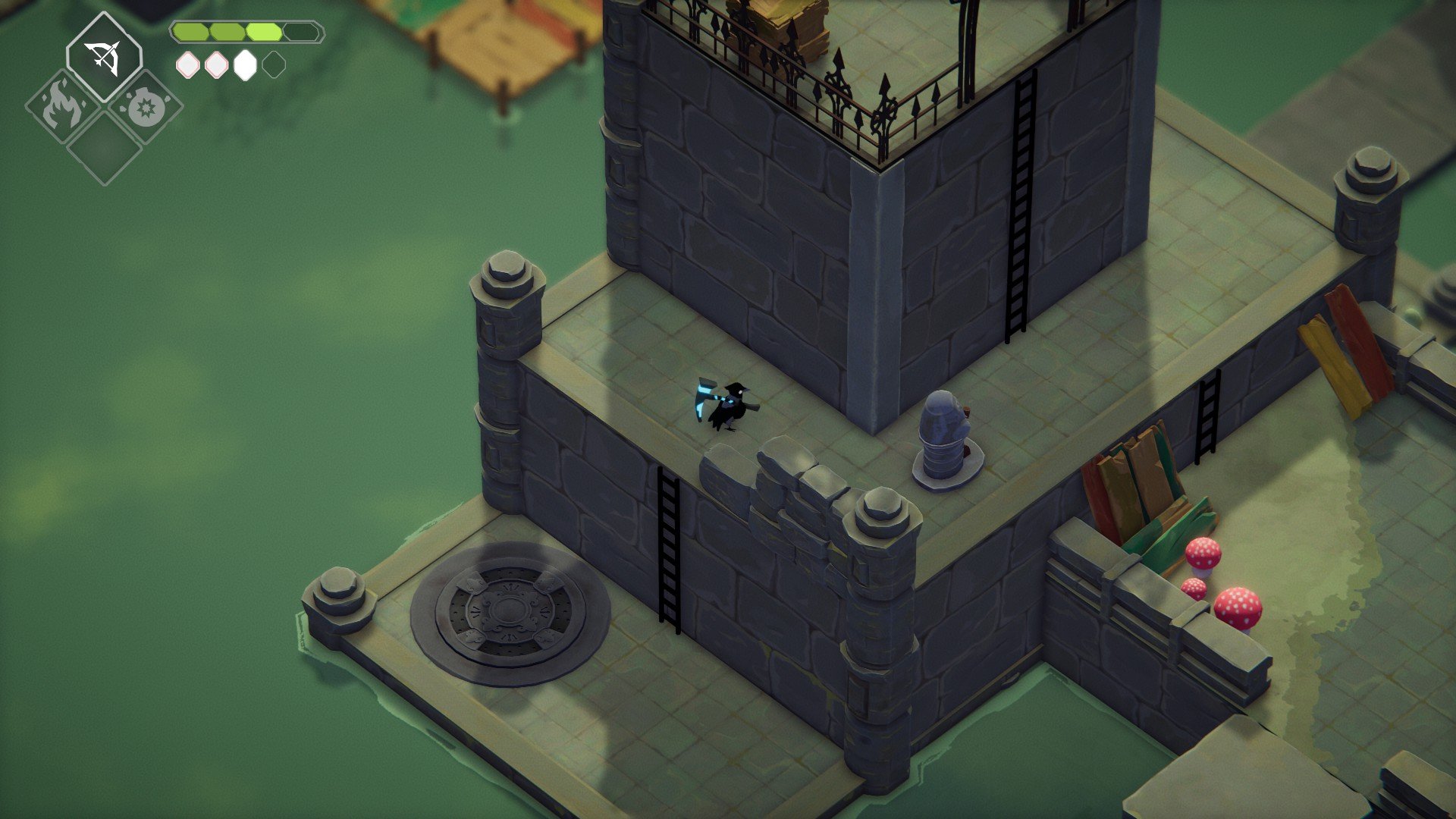

Death’s Door is a 2021 top-down action adventure game developed by Acid Nerve, published by Devolver Digital. A lot of the design principles draw from classic action adventure games like Zelda and some mechanical inspiration from Dark Souls, as well as building upon the two-person team’s previous game Titan Souls [2015]. Death’s Door sees the player as a Crow working at the Reaping Commission, and their assigned soul evades capture, leading to an adventure to collect three great souls across a sprawling world. The Crow gains new magic abilities throughout, which allow for additional exploration upon returning to previous areas, and the game rewards thorough exploration through weapons, seeds that can be planted for health pick-ups, and the various other collectibles and upgrades that can be found. The player will have to maneuver around or fight off enemies as they navigate the levels, some of which can be pretty challenging, pushing the player towards mastering combat to keep enough of the limited health for more exploring. Defeating enemies gives the player Souls, which act as the currency to level up each of the 4 stats, and unlike Dark Souls, the player does not lose these upon death, leading to a more forgiving progression system. Along the way the Crow will face off against many bosses and combat arenas, which are a ton of fun every time they come up.

The level design purposefully hides its full hand, often hinting at abilities that the player hasn’t received yet, encouraging more exploration to uncover everything they can with their current abilities. The enemies are spread just enough to keep the player active and aware, with the occasional crucible that will block the exits until the player defeats each wave successfully. This is a classic way to gate progression through skill-checks, if a little gamey, but when the combat is as fun as it is, it’s a blast every time. The game’s camera is a top-down, isometric perspective, with following behaviour that tracks a bit behind the player. The player can look around to move the camera a bit further, with the player still being visible no matter how far you try to push it. Sometimes the player will see something just barely out of view or hidden behind another object, and that limitation of the perspective is great for aiding exploration and discovery. On rare occasions however, the camera will turn to offer the player another view of a limited area, as shown below, usually leading to the discovery of a pick-up, once again amplifying the sense of discovery.

Areas are typically designed to allow the player to go through it quickly once cleared, often ending a section by opening a gate or releasing a ladder to a previous section, similar to Dark Souls level design principles. Once again drawing from that game, as the player progresses they will discover empty seed pots for health seeds to be planted in, meaning that the more the player explores to discover seeds, the more they can safely explore deeper in an area or continue exploring without the worry of losing health. There are a variety of ways that areas will open up, with ladders, levers, objects that open gates when hit, and enemies that can blow open walls for you. This variety of opening up the world keeps exploration all the more interesting, and often offers some puzzle solving possibilities to the player to progress. In line with moving the Crow around the world, there’s some great juice with walking leaving behind poofs of smoke and dodging leaving some feathers floating to the ground, which help make even the act of moving around fun and engaging.

I’ve been writing a lot about combat, so let’s dive a bit deeper into it. The Crow starts off with a sword and a magic bow as offensive options, with the sword having a three-hit combo light attack and a charged attack that can be combined with a dodge roll for a third melee attack type. As the game goes on, the player will find more melee weapons with different light attack combos and swing speeds, and different spells that provide use outside of combat (the fireball spell attained early on can be used to burn cobwebs blocking doorways or ladders, the bomb can blow apart cracked walls, and the hookshot unlocks loads of new areas to explore). Each of the spells, with the sole exception of the hookshot, have limited uses, with additional charges gained by hitting enemies or certain environment objects, incentivizing the player to stay in melee combat, weaving in and out to optimize the powerful spell usage. On getting hit, the player has a brief window of invincibility to avoid annoying instances of taking massive damage from multiple enemies at once, which is very welcome when the player only has four hit points to start with.

With combat and exploration being the two gameplay pillars of the game, the player will come across a lot of enemies in their journey. Typically the common enemies will only have a few attack behaviours, and each enemy is usually introduced either alone or with multiple of the same type, offering an opportunity for the player to learn their attack patterns before they fight in a larger arena with multiple enemy types. The more complex enemies with more than one attack behaviour are often a miniboss before they are added to combat encounters alongside common enemies, meaning that the player will constantly be faced with increasingly challenging scenarios. Most of the enemies utilize melee attacks with a few ranged enemies and some with both attack types, meaning that combat encounters with a variety of enemies will always keep the player moving and on their toes to avoid overlaps in attack patterns. The enemies are surprisingly reactive too, with damage appearing in the form of red lines on the model, showing the player at a glance how close they are to defeat, and some can even have parts of themselves fall off or break, like wooden shields or helmets on some bigger foes.

To wrap up the section on the game design, Death’s Door offers a great blend of accessible Zelda-like world progression and exploration, and its Dark Souls design influence in the combat and objective focus, leading to a very fun game with a lot to offer over its runtime. My playthrough to reach 100% completion topped out at 16 hours with writing notes and adding to the audio spreadsheet, but each hour was fun, which is ultimately the most important thing.

Moving on to the audio in Death’s Door, the thing that struck me the most, particularly for the game’s scope, was the attention to detail in the environmental sounds, with most sounds only varying based on pitch randomization instead of multiple variations, but the sheer amount of bespoke sounds for some things that only appear once or are only played in very specific situations was great to see. Things like lighting arrows on fire, bodies falling into water, and bumping into certain environment objects like mushrooms, bushes, and through leaves really lend a sense of realism to the world purely from seeing and hearing it react to your actions in a realistic manner. Certain environmental objects like wooden boxes, mushrooms, ceramic pots, and ice crystals can take damage and break, and some of those can respawn as well, with each of these actions (hit, break, and respawn) having a corresponding cue. The hub level stuck out to me as well for having a lot of unique environmental sounds, leading a Forest Spirit through the metal detector or going through it yourself produce two different sounds, Crows typing away on typewriters, and the whoosh of a ceiling fan all make this otherworldly, ethereal space feel lived in and real.

Ambiences naturally vary from location to location, and will crossfade quickly when moving between locations with the music, with both tracks playing through the fast loading screen to prepare the player’s ear for the new area. Music will also transition quickly when entering and exiting combat, and stingers will play when the player either dies or picks up an item. The music combined with the ambiences set the tone for each area excellently, and crossfading the tracks on loading screens is a great way to make travelling around this world feel more seamless.

As mentioned in the design section, enemy characters only usually have a few different attacks, but have different tells for each, whether it’s an attack windup or a sound for spotting the player. In the combat arenas, enemies will typically spawn in via doors that appear, and with the enemy counts sometimes reaching several enemies to keep track of, limiting the soundscape to just footsteps, their actions, and getting hit or dying leaves a lot of room for the player’s sounds to fill in the rest. The enemies have a normal sound for getting hit, but when taking fire damage it will play an additional burning sound for every tick that they take damage. Lastly for the enemies, as I point out in the notes on the spreadsheet screenshot, not every enemy has a sound cue for spotting the player, as it’s more necessary for some enemy types than others, but I may have missed times where it might have played.

The player sounds are limited to just a few movement actions, with weapon and spell sounds taking up much more audio real estate. The core movement actions of footfalls, rolling, getting hit, and dying all have their associated cues, with footsteps having variations for brick floors, ceramic tiles (reused for ice), grass and dirt, and possibly others I missed during my gameplay. When the player gets hit, I noticed that sometimes, often when either a boss or a bigger enemy hits the player, the whole soundscape gets ducked, likely with a low pass filter sweep. Hilariously, when later in the game the player picks up a squid named Jefferson for a stroll across the map, the footsteps, rolls, and attacking sounds all gain an additional squid noise, whether it’s a squeak as its tentacles flop around or a vocalization as it gets squished briefly.

Moving back to combat, weapon and spell sounds offer a lot of variety to what the player hears depending on what they use. Each of the four spells (the bow, the fireball, the bomb, and the hookshot) consist of four cues: charge and release for the player’s inputs for the spell, and the flight and impact cues for the projectile. Interestingly, the charge sound isn’t a loop, instead being a one-shot that fades out after fully charging, but the flight sound does seem to be a loop. The two spells with additional sounds are the bow, with one-shots for lighting and shooting fire arrows using environmental flames and supercharging with the upgrade, and the hookshot, with a special melee attack used when using the hookshot. On the topic of melee, there are five melee weapons found throughout the game, the sword, umbrella, daggers, hammer, and greatsword, with each having different swing sounds and combo end sounds. The melee weapons also have a charge attack, with a one-shot for charging and releasing that attack, as well as rolling attacks, parries for incoming projectiles, and a plunging attack, each of which having their own unique sounds per weapon. The one melee weapon with an additional sound is the fun umbrella weapon, which has a sound for when it opens after attacking or doing another action. With a combat encounter wrapped up, the final hit taking out an enemy slows down sounds for a few seconds, being a nice reward for the tougher combat gauntlets.

The UI for this game only has a few non-standard cues, like the dialogue continue, scroll, and exit, with the continue and exit being shared with the general UI forward and back respectively, and the scroll looping until the character finishes their line of dialogue. Notably for equipping different weapons and switching spells there is only a single cue each, so having equipping sounds for each individual weapon and spell would help add more variation and would add to the accessibility side of the game.

To wrap up, most sounds have minimal pitch variation, and most of the gameplay sounds that the player hears often like footsteps and sword swings seem to have a good amount of variations to keep ear fatigue at bay. The only other noticeable part of the implementation was that when the player pauses the game, it appears to just gently low-pass and lower the volume of the music and ambiences.

Thank you for reading this long look at the game design and sound design of Death’s Door. I really enjoyed my time with the game and I hope that if you haven’t played it yet that you give it a shot since it’s a charming and fun experience with a lot of soul. Please check out my previous Design & Sound deep dive on Armored Core VI: Fires of Rubicon if you found this interesting or insightful, or whatever other dives I might’ve written by this point that you’re reading this here.